Trubutes to Edward Branigan

Most of you know me by one of the many hats I wear: art historian, architectural historian, travel writer, tour guide, teacher. But my first book was a reissue of a book of film theory, Hugo Munsterberg’s ‘The Photoplay, a Psychological Study’. This is on my mind today as that book was made possible by a remarkable man who we’ve had to say goodbye to this weekend: Edward Branigan, one of the world’s foremost film theorists. As a graduate student, I worked for several quarters as Edward’s Teaching Assistant in his famous course ‘Classical Film Theory’, a course which, for the past fifteen years, I have had the honor to continue teaching at U. C. Santa Barbara

during the summers after Edward’s retirement. I’m in the midst of teaching it now. Edward’s teaching

style was memorable. The chalk boards were always filled, erased, filled again. The flow of his

ideas, and the ideas of the students, were part of an enthusiastic exchange that was ever-changing

and leading in provocative directions. PowerPoint would have killed his class. His classes at UCSB’s

Film Studies department were intellectually challenging. He refused to ‘dumb down’ his course

content, instead having unwavering faith in the intellectual capacities of the students. He won

UCSB’s Distinguished Teacher award in 1997. After serving in Vietnam Edward had begun his

career as a lawyer, but his interest in film made him give it all up to study the medium he loved.

Edward could meet people from any continent or country in the world and immediately engage them

in a conversation about their country’s cinematic masters. He was an omnivorous intellectual, and,

uncommon for an academic, he liked listening to people. He loved people, he loved ideas, he loved

how film enriched life. Edward’s book ‘Narrative Comprehension and Film’ (1992) won the Kovacs

Prize for cinema studies. He also published, in 2006, ‘Projecting a Camera: Language Games in

Film Theory’, and was, with Warren Buckland, the editor of the ‘Routledge Encyclopedia of Film

Theory’ (2015). Along with his colleague at UCSB Chuck Wolfe, he edited the well-known Routledge

volumes for the American Film Institute. His other books included ‘Point of View in the Cinema’

(1985), and ‘Tracking Color in Cinema and Art’ (2017). He published dozens of articles, many of

them classics, such as “The Space of Equinox Flower”, on the film by the Japanese filmmaker Ozu

Yasujiro, printed in ‘Screen’ in 1976. I will miss Edward. He is one of the people who had a dramatic

influence on my development and my attitudes towards scholarship, learning, and teaching.

Goodbye Edward. You were a wonderful person to know, and, when I get up in front of my Classical

Film Theory students on Tuesday, you will be very much on my mind. I will try, as always, to keep

your spirit alive.

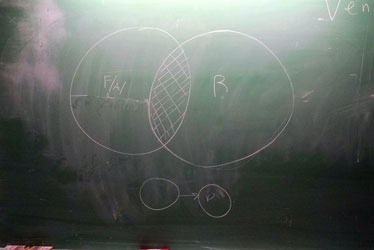

Today I gave a lecture on Arnheim’s Film as Art in Buchanan 1920 at UCSB, the same lecture hall

Edward Branigan taught Classical Film Theory in for so many years. I noted to my TA that 25 years

before I was sitting where he was sitting, and I felt, once again, honored to be teaching the course

Edward taught here in this very room for so many years. For us old school teachers, one of the

things we always did as a courtesy for those who would teach afterwards was to erase everything

from the chalk boards. I was doing the same today after the students had left, the vacuum of their

departure tangible, but when I came to this Venn diagram I paused, eraser hovering. I put it down. I left up one last Abstraction / Reality Venn diagram for Edward. I imagined for a moment all of his

years of writing on that board, and all of mine, still there, atomic particles, traces of a life of teaching,

overlapping, passing on a love of learning from one generation to the next. You cannot erase

teaching. As I left I turned out the lights, and into the darkness said goodbye to Edward.

Most of you know me by one of the many hats I wear: art historian, architectural historian, travel writer, tour guide, teacher. But my first book was a reissue of a book of film theory, Hugo Munsterberg’s ‘The Photoplay, a Psychological Study’. This is on my mind today as that book was made possible by a remarkable man who we’ve had to say goodbye to this weekend: Edward Branigan, one of the world’s foremost film theorists. As a graduate student, I worked for several quarters as Edward’s Teaching Assistant in his famous course ‘Classical Film Theory’, a course which, for the past fifteen years, I have had the honor to continue teaching at U. C. Santa Barbara

during the summers after Edward’s retirement. I’m in the midst of teaching it now. Edward’s teaching

style was memorable. The chalk boards were always filled, erased, filled again. The flow of his

ideas, and the ideas of the students, were part of an enthusiastic exchange that was ever-changing

and leading in provocative directions. PowerPoint would have killed his class. His classes at UCSB’s

Film Studies department were intellectually challenging. He refused to ‘dumb down’ his course

content, instead having unwavering faith in the intellectual capacities of the students. He won

UCSB’s Distinguished Teacher award in 1997. After serving in Vietnam Edward had begun his

career as a lawyer, but his interest in film made him give it all up to study the medium he loved.

Edward could meet people from any continent or country in the world and immediately engage them

in a conversation about their country’s cinematic masters. He was an omnivorous intellectual, and,

uncommon for an academic, he liked listening to people. He loved people, he loved ideas, he loved

how film enriched life. Edward’s book ‘Narrative Comprehension and Film’ (1992) won the Kovacs

Prize for cinema studies. He also published, in 2006, ‘Projecting a Camera: Language Games in

Film Theory’, and was, with Warren Buckland, the editor of the ‘Routledge Encyclopedia of Film

Theory’ (2015). Along with his colleague at UCSB Chuck Wolfe, he edited the well-known Routledge

volumes for the American Film Institute. His other books included ‘Point of View in the Cinema’

(1985), and ‘Tracking Color in Cinema and Art’ (2017). He published dozens of articles, many of

them classics, such as “The Space of Equinox Flower”, on the film by the Japanese filmmaker Ozu

Yasujiro, printed in ‘Screen’ in 1976. I will miss Edward. He is one of the people who had a dramatic

influence on my development and my attitudes towards scholarship, learning, and teaching.

Goodbye Edward. You were a wonderful person to know, and, when I get up in front of my Classical

Film Theory students on Tuesday, you will be very much on my mind. I will try, as always, to keep

your spirit alive.

Today I gave a lecture on Arnheim’s Film as Art in Buchanan 1920 at UCSB, the same lecture hall

Edward Branigan taught Classical Film Theory in for so many years. I noted to my TA that 25 years

before I was sitting where he was sitting, and I felt, once again, honored to be teaching the course

Edward taught here in this very room for so many years. For us old school teachers, one of the

things we always did as a courtesy for those who would teach afterwards was to erase everything

from the chalk boards. I was doing the same today after the students had left, the vacuum of their

departure tangible, but when I came to this Venn diagram I paused, eraser hovering. I put it down. I left up one last Abstraction / Reality Venn diagram for Edward. I imagined for a moment all of his

years of writing on that board, and all of mine, still there, atomic particles, traces of a life of teaching,

overlapping, passing on a love of learning from one generation to the next. You cannot erase

teaching. As I left I turned out the lights, and into the darkness said goodbye to Edward.

Vale, dear Edward Branigan. I will forever cherish the time I spent in your classroom and as your teaching assistant at UCSB. You made time (“Time!!” as you were so fond of saying) for everyone, listened and always encouraged all of us to publish our work. Your support of your students helped all of us to believe in our own ideas more, and to continue to challenge ourselves and create. I will cherish even more so our long and impromptu email exchanges that continued in the years since we both left UCSB. They were less about film studies and more about life, and always with a philosophical and tender twist. Our last few exchanges occurred when you were dealing with the loss of your house to a California wildfire and then with the all consuming cancer. I marveled at you rising like a Phoenix from the ashes of that fire; you lost all of your possessions, but still had your family and your health, and moved on to a new city with a new partner at a time in life (your early 70s) when most wouldn’t have that resilience. The one thing you said it pained you to lose in that fire was your collection of letters from Vietnam, from comrades who had written home to you after your tour of duty had ended, and your own letters home that your loved ones had saved for you. Most of your other writing was published and quoted a thousand times over, but not these words. You were unlike any other professor I know in terms of your path: a soldier in Vietnam, then a lawyer, then a film theorist. Yes you had the beard and the rumpled shirts and ties and likely even a proper elbow-patched tweed blazer, and you enjoyed playing with these tropes and delighting the undergrads with your affected “absent minded” professor routine. But you were never absent, you were always present, and faced the present. In our last exchanges you talked most about being tired, and how the treatments were taking their toll, but even then you continued to send the

ever-growing list of your grad alums e-mails with info about conferences and publishing opportunities. Till the end you made time for others, and I do believe you made the most of your time here on this earth. Thank you, irreplaceable Edward. 💜 ❤

I came to know Edward as a student when I took his Film Theory 192A course in 1996, and afterwards he invited me to be a teaching assistant for the class. We stayed in touch over the years after, developing a friendship primarily via electronic correspondence.

As anyone who took a class with him or worked with him would know, Edward really was both an iconoclastic, quintessential professor, donning the professorial costume, with the slightly (but perfectly) disheveled hair, and wild enthusiasm for the subject matter, equaled only by exuberant gestures. He was also special in that like many of the other professors in the Film Studies department at UCSB (Chuck Wolfe, of course) he had zero pretense – he was too busy loving the work and sharing ideas. As his teaching assistant, a mere recent graduate and all of 21 years old, I was treated by Edward not as a subordinate (as I had expected), but with respect, and I learned early on that an essential component of teaching was listening.

Few moments from my undergrad years stood out as sharply as Edward’s lecture on André Bazin. As he later recalled in an email – “Ah, the bug in the amber. This was part of my argument in explaining Bazin, i.e., how photography (and film) is essentially a preservative medium. Point the camera, get reality. Kindest, E.” No one could bring film theory to life the way he did. Perhaps few could bring life to life, as he did.

If digital technology, particularly email, is an enemy of society with respect to human relationships, he conquered the medium. His digital correspondence maintained the qualities of a letter. He did not write an email, he composed a letter. Edward captured and maintained the ethereal quality of written communication, which he preserved, like the bugs trapped in amber.

Edward Branigan was a dazzlingly brilliant film theorist who understood how language shapes our thinking, and our thinking about film, better than anyone else I know. When I decided to apply to grad schools, hoping to study the language of film theory, we were naturally drawn to each other. I pursued my PhD in Film Studies under his supervision at UCSB, which was starting up a new PhD program that he was directing at the time. While there, my interests shifted, and he followed and supported me every step of the way—unconditionally, with generosity, and with an open mind. He never had a single negative thing to say about anything I did (though he certainly could have found plenty) and had a way of always focusing on the positive elements of an idea to nurture and expand.

Edward Branigan was a dazzlingly brilliant film theorist who understood how language shapes our thinking, and our thinking about film, better than anyone else I know. When I decided to apply to grad schools, hoping to study the language of film theory, we were naturally drawn to each other. I pursued my PhD in Film Studies under his supervision at UCSB, which was starting up a new PhD program that he was directing at the time. While there, my interests shifted, and he followed and supported me every step of the way—unconditionally, with generosity, and with an open mind. He never had a single negative thing to say about anything I did (though he certainly could have found plenty) and had a way of always focusing on the positive elements of an idea to nurture and expand.

My inbox is filled with thousands of emails from him, almost all signed with a single word– “Kindest”–followed by “E.” Some messages include photos with one of his four sons or of mountains, trees, and wildlife in Bellingham, Washington, where he had recently moved; a lot are forwarded messages from “Filmies” (a listserv circulated amongst UW Madison Film Studies alumni and students; he was a proud student of David Bordwell); some are cryptic or poetic musings; and some include essay-length comments he’d write in response to comments I’d left for him on drafts of essays and longer manuscripts, including his recent masterful book on color. Many contain tips on films to watch or books to read. Most in some way are part of ongoing exchanges about language or theory.

Edward was a truly legendary lecturer, performing with an unbounded, zany, Coca-Cola-caffeinated energy every time he stepped in front of his students. He brought classical film theory to life in scenes that themselves felt lifted out of movies—covering cluttered chalkboards with illustrations, outlines, a recurring cast of characters, and ideas. As Regina Longo writes, he performed the “absent-minded professor routine,” but was in fact always very present, always fighting against the onward march of time and never aware of how much time would pass while in your presence, listening to you attentively. He notoriously didn’t include screenings in his Classical Film Theory class, which I was his teaching assistant for twice, but his ability to analyze a scene from a film, and explain how moving images and sounds make meaning, could be mind-blowing. Students ate it up, learning so much in the process not only about film but about philosophy and life itself. Singer and UCSB film studies alum Jack Johnson even credited him with inspiring his very first song, “Inaudible Melodies,” which references Plato’s cave, Eisenstein, silent film, and narratology (how many other film theorists can claim to have inspired a pop song?). But this is just the tip of the iceberg; he inspired thousands of students intellectually and creatively, many of whom have become scholars and filmmakers. I will forever cherish my memories of working as his TA and witnessing his powerful, lingering effect on students in seminars.

Like many teachers, students, family, and colleagues whose paths have crossed with Edward’s, I’ve learned immeasurably from him. It was a special, formative privilege to have been mentored by this one-of-a-kind scholar. Before he was diagnosed with cancer, he often invited me to visit him in Washington, suggesting that we’d been “piling up” stories to tell. I wish he’d stayed well longer so that I could have come and shared stories—mostly to hear his. I’ll miss him, his emails, and his gentle, guiding presence in my life so much.

Jack Johnson’s Inaudible Melodies

Itsy bitsy diamond wells

Big fat hurricanes

Yellow bellied given names

Well shortcuts can slow you down

And in the end we’re bound

To rebound off of we

Solar powered plastic plants

Pretty pictures of things we ate

We are only what we hate

But in the long run we have found

Silent films are full of sound

Inaudibly free

You’re moving too fast

Frames can’t catch you when

You’re moving like that

Serve narrational strategies

Unobtrusive tones

Help to notice nothing but the zone

Of visual relevancy

Frame-lines tell me what to see

Chopping like an axe

You’re moving too fast

Frames can’t catch you when

You’re moving like that

Demanding refunds for the things they’ve seen

I wish they could believe

In all the things that never made the screen

And just slow down everyone

You’re moving too fast

Frames can’t catch you when

You’re moving like that

Slow down everyone

You’re moving too fast

Frames can’t catch you when

You’re moving like that

Moving too